Historical Highlights

Kingdom of Mauretania (c. 110 BCE – 44 CE)

Not to be confused with modern Republic of Mauritania!

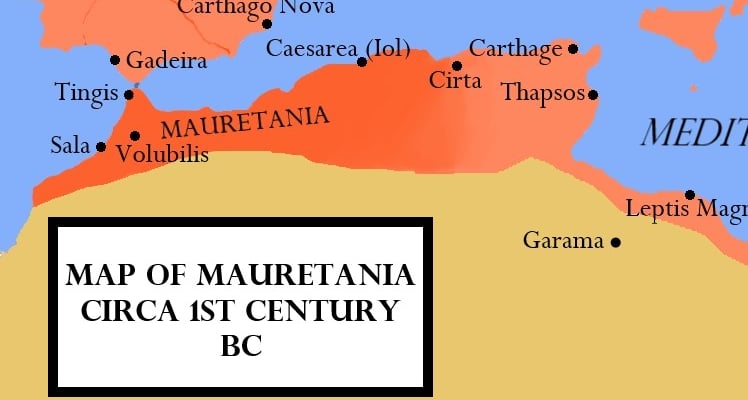

The Kingdom of Mauretania existed from around 110 BCE to 44 CE and was an important ancient Berber kingdom located in what is today northern Morocco and western Algeria. It should not be confused with modern-day Mauritania, which lies further south. The kingdom was ruled by the Mauri people, a Berber group from which the name "Mauretania" is derived.

Initially independent, the kingdom played a significant role in regional politics and gradually came under the influence of the Roman Republic. During the late Republican and early Imperial periods, Mauretania became a client state of Rome, strategically important for controlling North Africa’s Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

Several notable rulers emerged from this era. Bocchus I allied with the Romans during the Jugurthine War (against Jugurtha of Numidia), earning Roman favor and territory. Later, Bocchus II ruled during a period of increased Roman alignment. Perhaps the most famous Mauretanian ruler was Juba II, the son of King Juba I of Numidia. After being raised in Rome following his father's defeat, Juba II returned to North Africa to rule Mauretania. He became a highly Romanized monarch—fluent in Latin and Greek, a prolific writer, and a promoter of Roman culture and architecture in the region. He also married Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII, symbolizing the merging of Berber, Roman, and Hellenistic legacies.

Under Juba II, cities like Volubilis, Tingis (modern Tangier), and Caesarea (in modern Algeria) flourished, reflecting a mix of local Berber traditions and Roman civilization. The kingdom prospered through agriculture, trade, and diplomacy.

Following the death of Ptolemy of Mauretania, the son of Juba II and Cleopatra Selene II, in 44 CE, the Roman Emperor Claudius annexed the kingdom. Mauretania was divided into two Roman provinces: Mauretania Tingitana, corresponding largely to northern Morocco, and Mauretania Caesariensis, covering parts of modern northern Algeria. This marked the end of Mauretanian sovereignty and the full integration of the region into the Roman imperial system.

Roman and Byzantine Rule (44 CE – 7th century)

From 44 CE to the early 7th century, present-day Morocco and the broader Maghreb were shaped by successive waves of imperial rule, beginning with the Romans, followed by the Vandals, and later the Byzantines.

After the death of King Ptolemy of Mauretania, the region of Mauretania Tingitana (roughly northern Morocco) was annexed by the Roman Empire in 44 CE. Under Roman rule, the area experienced relative peace and economic development. Roman cities like Volubilis, Tingis (Tangier), and Lixus became centers of trade, agriculture, and administration. Volubilis, in particular, flourished with its mosaics, temples, and olive oil production, serving as a cultural and economic hub connected to the rest of the empire.

By the early 5th century, the stability of Roman North Africa began to wane. In 429 CE, the Vandals, a Germanic tribe, crossed into North Africa from Spain. Their arrival marked the collapse of effective Roman control in the western provinces. Although the Vandals primarily settled in what is now Tunisia and eastern Algeria, their presence affected the whole region, including Mauretania Tingitana, leading to instability and the decline of urban life.

In 534 CE, the Byzantines (Eastern Roman Empire) reconquered parts of North Africa under Emperor Justinian I during his campaign to restore Roman territory. Although their control was mostly limited to coastal cities and strategic forts, they attempted to re-establish imperial authority and promote Christianity, especially in areas like Septem (modern Ceuta). However, their influence was limited, and the interior remained largely autonomous or under Berber control. The Byzantine period laid the groundwork for the complex religious and political dynamics that would precede the Arab-Islamic conquest in the 7th century.

Islamic Conquest and Early Islamic Dynasties (7th – 8th century)

The Islamic conquest of Morocco between 681 and 711 CE, led by Umayyad generals such as Uqba ibn Nafi and Musa ibn Nusayr, marked a significant turning point in the region's history. While many local Berber tribes gradually embraced Islam and adopted elements of Arabic culture, tensions simmered beneath the surface due to political marginalization and heavy taxation imposed by the Umayyad rulers. These grievances culminated in several revolts, most notably the Great Berber Revolt of 739–743 CE, which was a direct challenge to Umayyad authority. Sparked in part by the discriminatory treatment of non-Arab Muslims, this uprising spread across North Africa and severely weakened Umayyad control in the region. One of the most iconic figures of this era was Tarik Ibn Ziyad, a Moroccan Berber general who, under the Umayyad banner, famously led the Muslim army across the Strait of Gibraltar in 711 CE and initiated the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Tarik’s bold leadership and military success became a symbol of Moroccan valor and strategic brilliance. Ironically, while he expanded the Umayyad reach into Europe, the internal contradictions and injustices faced by people in North Africa—many of whom, like Tarik, were instrumental in the expansion—led to resistance that contributed to the weakening and eventual fall of the Umayyad dynasty. This period not only shaped Morocco’s Islamic identity but also laid the groundwork for future independent dynasties in north Africa.

Idrisid Dynasty (788 – 974 CE)

The Idrissid Dynasty was the first independent Islamic dynasty to establish lasting rule in Morocco, marking a key moment in the country’s early Islamic history. Founded in 788 CE by Idris I, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad through his grandson Hasan, the dynasty emerged during a time of great unrest in the Islamic world. Idris I fled the Abbasid Caliphate after the Battle of Fakhkh in 786 CE, seeking refuge in Morocco, where he was warmly welcomed by local Berber tribes, particularly the Awraba. With their support, he established a new Islamic polity that united much of northern Morocco under his leadership.

The Idrissids chose Fez as their capital, which quickly became a vibrant center of Islamic learning, culture, and trade. Under the rule of Idris II, the dynasty further expanded and consolidated power, strengthening Islamic institutions and fostering the growth of urban life. The Idrissid era was pivotal in anchoring Islam deeply within Moroccan society, blending Arab-Islamic traditions with Berber customs and laying the foundation for a uniquely Moroccan Islamic identity. Despite facing internal divisions and external threats, the dynasty’s legacy endures in Moroccan history as a symbol of independence, religious legitimacy, and the early formation of a unified Moroccan state.

Zenata and Other Berber Dynasties (10th – 11th century)

Following the decline of the Idrisid dynasty in the 10th century, Morocco entered a period marked by fragmentation and the rise of powerful local Berber dynasties, particularly from the Zenata confederation, such as the Miknasa, Maghrawa, and later the Ifrenids. These tribes, each with their own ambitions and territorial claims, took control of different regions, leading to a patchwork of rival principalities rather than a unified Moroccan state.

The Maghrawa, for instance, gained control of Fez, turning it into their political base and vying for dominance in northern Morocco. Meanwhile, the Miknasa, initially aligned with the Fatimid Caliphate, controlled parts of eastern Morocco and parts of present-day Algeria. The Ifrenids, a more militant and religiously zealous group, challenged both the Maghrawa and Miknasa, often engaging in open conflict.

This era of tribal rivalry and shifting alliances was marked by frequent wars and instability, but it was also a time when Berber identity and political autonomy became more pronounced. These dynasties, despite their rivalries, maintained and developed Islamic governance, trade networks, and urban centers inherited from earlier periods. While the political landscape was divided, the groundwork was being laid for the rise of more centralized and powerful Berber dynasties such as the Almoravids and Almohads, who would eventually restore unity and bring Morocco onto the larger stage of Islamic and Mediterranean history.

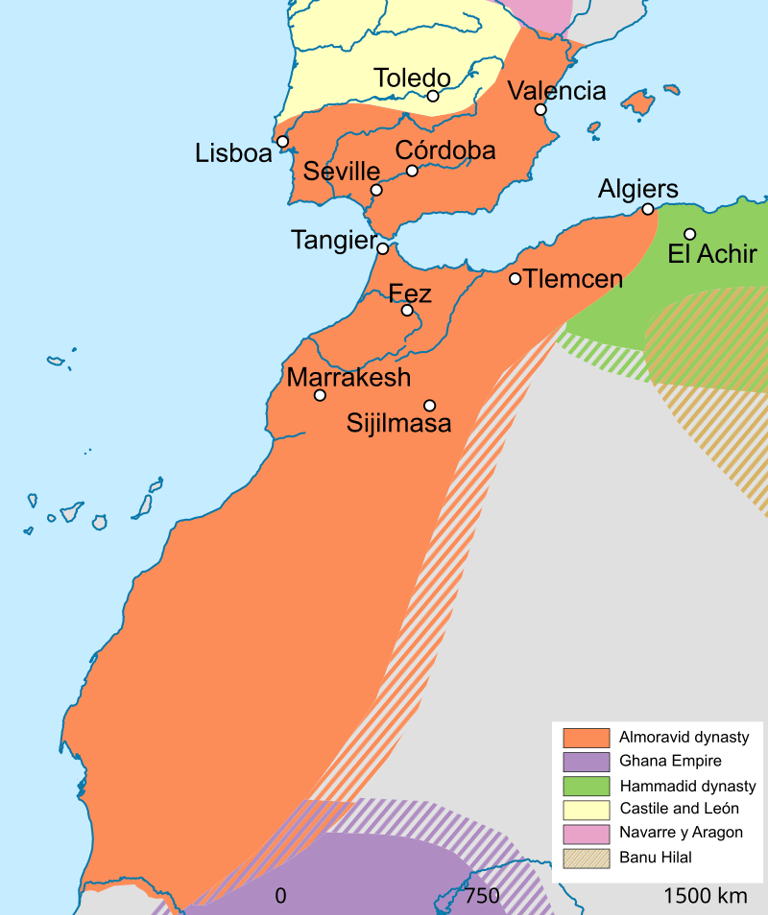

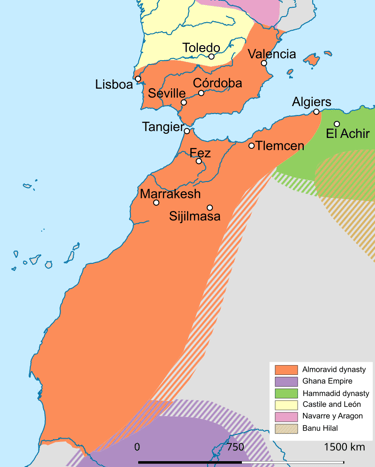

Almoravid Dynasty (1040 – 1147)

The Almoravid dynasty (11th–12th century) was a powerful Berber empire that rose from humble beginnings in the Sahara Desert to become one of the most formidable Islamic forces of its time. Founded by Abdallah ibn Yasin, a zealous religious reformer of the Maliki school, the movement began as a call for purifying Islam and uniting the fragmented Berber tribes of the Sanhaja confederation under a strict interpretation of Islamic law. What started as a spiritual revival quickly transformed into a major political and military campaign, laying the foundation for a vast empire.

The true architect of the Almoravid Empire’s glory was Youssef Ibn Tachfin, a brilliant military leader and statesman who succeeded in transforming the movement into a sophisticated and powerful state. In 1062, he founded the city of Marrakech, which would become a thriving capital, renowned for its architecture, scholarship, and trade. Youssef Ibn Tachfin’s most legendary achievement was his intervention in Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), where the once-glorious Muslim kingdoms had fallen into decline and disunity, weakened by internal rivalries and threatened by the advancing Christian Reconquista.

Responding to pleas for help from the Andalusian rulers, Youssef Ibn Tachfin crossed into Spain and decisively defeated the Christian forces led by Alfonso VI of Castile at the Battle of Sagrajas (Zallaqa) in 1086, a turning point that saved Al-Andalus from collapse. More than just a warrior, he was a unifier—restoring order in both North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. Under his rule, the Almoravid Empire extended from Senegal to the Ebro River in Spain, creating a vast transcontinental domain that promoted Islamic scholarship, architectural development, and trade across the western Islamic world.

Youssef Ibn Tachfin is remembered as a just and pious ruler, deeply respected for his humility, intelligence, and dedication to Islam. His leadership not only saved Al-Andalus from imminent conquest but also elevated Morocco to the status of a major Islamic power with influence stretching across Africa and Europe. His legacy laid the groundwork for the continued cultural and religious connections between Morocco and Al-Andalus, and his reign is regarded as one of the golden chapters of Moroccan history.

Almohad Dynasty (1147 – 1269)

The Almohad Dynasty (1147–1269) stands as one of the most glorious and powerful chapters in Moroccan and Islamic history. Founded by Ibn Tumart, a visionary religious reformer from the High Atlas Mountains, the Almohads rose with a mission to purify the faith and restore unity across the Islamic world. Fueled by spiritual fervor and a disciplined following, they decisively overthrew the Almoravids and built an empire of breathtaking scale—stretching from Libya in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west, and from the Sahara Desert in the south to the heart of Al-Andalus in Spain.

Under the brilliant leadership of Abd al-Mu’min, the first Almohad caliph, and his successors, the dynasty forged a transcontinental empire that united all of North Africa—from Tripoli to Marrakesh—under a single banner. Their dominion extended deep into southern Spain, where they stood as the final shield protecting the Muslim presence in Europe. The Battle of Alarcos in 1195, led by Caliph Yaqub al-Mansur, was a stunning victory that halted the Christian advance and reaffirmed Almohad dominance in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Almohads were not only conquerors but patrons of knowledge, architecture, and culture. Their reign was marked by a golden age of science, philosophy, and arts, where towering intellectuals like Ibn Rushd (Averroes) and Ibn Tufail flourished under their protection. Cities such as Marrakesh, Seville, and Rabat blossomed with majestic mosques, fortified walls, and soaring minarets—testaments to the dynasty’s vision and grandeur. The Almohad era was a beacon of Islamic enlightenment and unity, where power and piety walked hand in hand, and where Morocco stood proudly as the heart of a mighty empire that shaped the fate of two continents.

The legacy of the Almohads continues to inspire awe: they were not only defenders of faith and unifiers of the Maghreb, but also torchbearers of civilization at a time when the Islamic West reached its zenith of power, influence, and cultural brilliance.

Marinid Dynasty (1244 – 1465)

The Marinid Dynasty (1244–1465) marked a vibrant and transformative era in Moroccan history, rising to prominence in the aftermath of the Almohad decline. Originating from the Zenata Berber tribes, the Marinids positioned themselves as both defenders of Islam and revivers of Moroccan sovereignty. They successfully captured Fes in 1248, making it their capital and the cultural heart of their empire. Under their rule, Morocco experienced a golden age of education, architecture, and diplomacy, while asserting strong influence across the Maghreb.

The Marinids extended their control over large parts of Algeria and Tunisia, and for a time, reasserted power in Al-Andalus by supporting the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada against the Christian Reconquista. Though their control in Spain was not as long-lasting as their Almohad predecessors, their involvement helped preserve Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula during critical times.

What truly set the Marinid era apart was its commitment to intellectual and religious life. The dynasty constructed spectacular madrasas (Islamic schools), most notably in Fes, which became one of the most celebrated centers of Islamic learning in the Muslim world. Institutions like the Bou Inania Madrasa and Al-Attarine Madrasa stand to this day as masterpieces of Marinid architecture—famed for their intricate tile work, calligraphy, and spiritual ambiance.

Despite political instability in later years and growing European pressure along the Atlantic coast, the Marinids left behind a legacy of urban development, artistic flourish, and educational advancement. Their reign was the last great Berber dynasty before the rise of the Wattasids and later the Saadians, and it represents a proud chapter where Moroccan identity, Berber heritage, and Islamic scholarship flourished hand in hand.

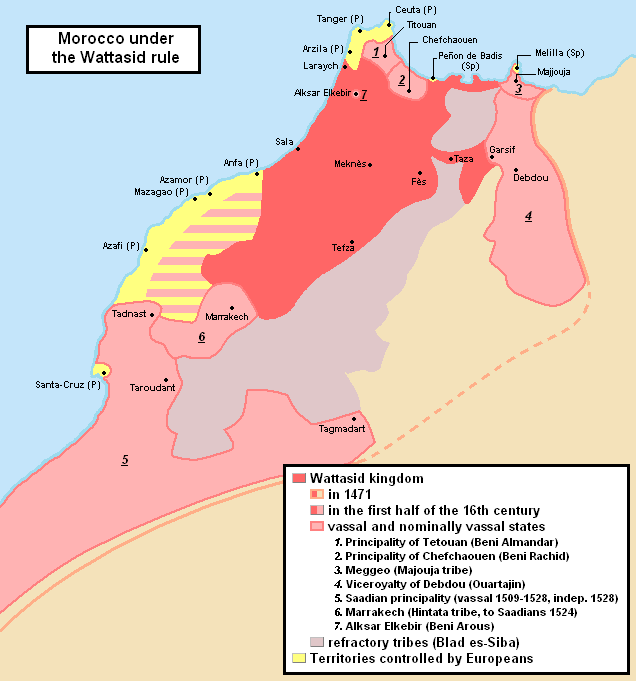

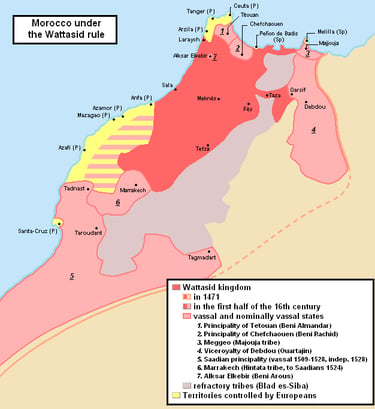

Wattasid Dynasty (1472 – 1554)

The Wattasid Dynasty (1472–1554) emerged during a period of great political fragmentation and external threats, yet managed to uphold Morocco’s independence and cultural continuity at a time when much of the Islamic world was in turmoil. Descended from the Marinids and originally their viziers, the Wattasids assumed full control after the Marinid decline, establishing their rule over northern Morocco with Fes as their capital.

Though constantly challenged by internal rebellions and rival claimants—especially the rising Saadians in the south—the Wattasids demonstrated resilience in navigating a complex political landscape. Their reign coincided with the expansion of European powers along the Moroccan coast, particularly the Portuguese and Spanish, who had captured several strategic port cities. Despite limited military capacity, the Wattasids skillfully used diplomacy to preserve Morocco's territorial integrity, often negotiating truces to safeguard their rule.

Culturally, the Wattasid period was one of intellectual perseverance, maintaining the scholarly legacy of Fes as a religious and academic beacon. Though their political power waned over time, the dynasty continued to support religious institutions, Sufi orders, and centers of learning. They also played a crucial transitional role in preserving Morocco’s identity between the great Berber dynasties and the rise of the Saadian Empire.

Ultimately, the Wattasids were overthrown by the Saadians, whose militarized and religiously driven leadership promised stronger resistance against Iberian colonial ambitions. Yet the Wattasids remain a vital link in Moroccan history—a dynasty that, even in the face of adversity, safeguarded the soul of the nation and laid the groundwork for the powerful resurgence that would follow.

Saadian Dynasty (1549 – 1659)

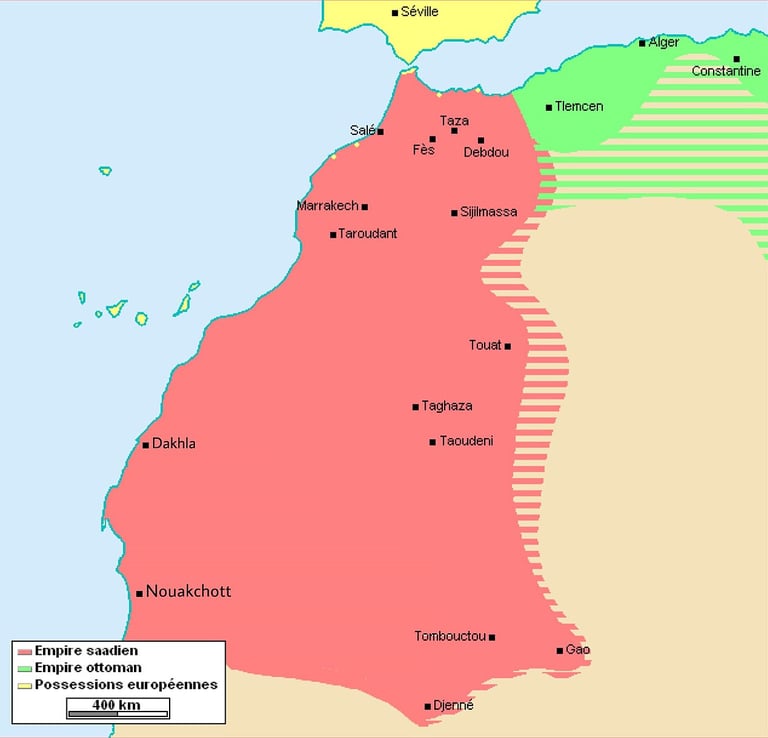

The Saadian Dynasty (1549–1659) shines as one of the most illustrious and powerful chapters in Moroccan history, marking a golden age of independence, religious legitimacy, military strength, and cultural brilliance. Claiming Sharifian descent from the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), the Saadians emerged as both spiritual and political leaders during a time when Morocco faced threats from foreign invaders and internal division.

Rising from the southern city of Taroudant, the Saadians quickly gained popular support for their mission to liberate Morocco from Portuguese and Spanish encroachment. Their defining moment came with the Battle of the Three Kings in 1578, also known as the Battle of Wadi al-Makhazin (Battle of Alcacer Quibir). In this monumental victory near the town of Ksar el-Kebir, Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur and the Moroccan army crushed a large Portuguese-led force, resulting in the death of three monarchs—King Sebastian of Portugal, Sultan Abu Abdallah Mohammed, and Sultan Abd al-Malik. This victory not only secured Morocco's sovereignty but also stunned Europe and affirmed Morocco's role as a formidable power in the Islamic world.

Under the rule of Ahmad al-Mansur (r. 1578–1603), known as "al-Dhahabi" (the Golden One), the Saadian Empire reached its zenith. His reign brought unprecedented prosperity through the trans-Saharan gold trade, sophisticated diplomacy with both the Ottoman Empire and European powers, and an ambitious program of architectural development. Al-Mansur’s ambition even extended to launching a military expedition that captured Timbuktu and parts of the Songhai Empire, thus expanding Moroccan influence deep into West Africa.

The Saadian capital, Marrakech, became a glowing center of power and culture. The dynasty left behind some of Morocco’s most iconic architectural masterpieces, such as the Saadian Tombs, the stunning El Badi Palace, and the elaborately decorated Ben Youssef Madrasa. These structures reflect the dynasty’s refined artistic sensibility, blending Andalusian, Berber, and Islamic influences into breathtaking expressions of Moroccan identity.

Despite internal succession struggles after al-Mansur's death and growing regional instability, the Saadian legacy endures. Their reign not only preserved Moroccan independence during a period when much of the Muslim world was falling under Ottoman or European control, but it also elevated Morocco to international prominence through trade, architecture, military achievement, and religious authority.

The Saadians were more than just rulers—they were protectors of the faith, champions of the nation, and architects of a flourishing Moroccan state that stood proudly between the Mediterranean, the Sahara, and the Atlantic. Their dynasty continues to inspire national pride and remains a symbol of Morocco’s resilience, glory, and enduring connection to both its Islamic and African roots.

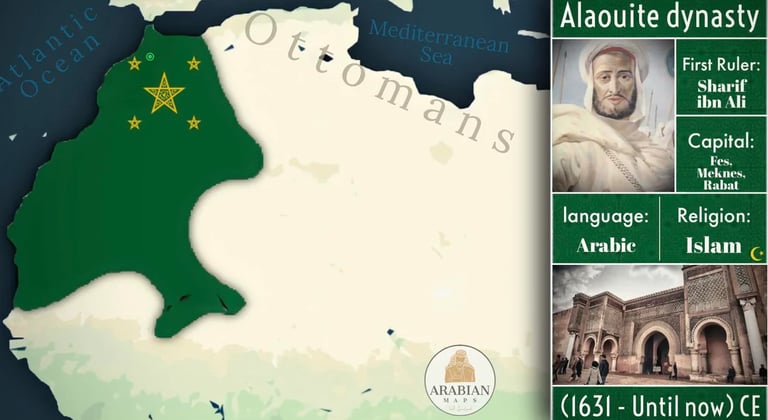

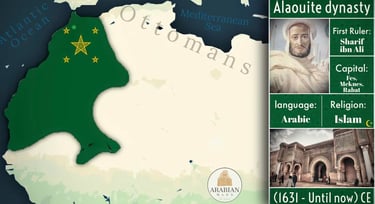

Alaouite Dynasty (1631 – 1830)

The Alaouite Dynasty (1631–1830) represents a pivotal and enduring chapter in the history of Morocco, marked by resilience, unity, and the safeguarding of Moroccan sovereignty. Descended from the Sharifian lineage, the Alaouites trace their ancestry back to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), a lineage that granted them religious and political legitimacy. The dynasty rose to power during the early 17th century, a period of internal strife and fragmentation following the decline of the Saadian Dynasty.

The Alaouites emerged as unifiers in a fractured Morocco, establishing a strong centralized authority in the face of tribal rivalries, external threats, and regional conflicts. Under the leadership of Moulay Rachid (reigned 1666–1672), the Alaouites solidified their control over the country. His successor, Moulay Ismail (reigned 1672–1727), expanded the Alaouite influence and strengthened the monarchy, fostering stability across the realm. Known for his remarkable military leadership, Moulay Ismail built a powerful army that helped maintain order and curb the influence of rebellious tribes, securing the unity of Morocco and ensuring the dynasty’s continued dominance.

The Alaouite rulers were adept at balancing diplomacy and military strength, navigating the complexities of both domestic and foreign affairs. Under their reign, Morocco witnessed the flourishing of urban centers like Marrakech and Fes, which became hubs of culture, trade, and Islamic scholarship. The Alaouites ensured that Moroccan society remained firmly anchored in its Islamic identity while fostering artistic and architectural achievements that enriched the country’s cultural heritage.

By the 18th century, the Alaouites had successfully maintained the sovereignty of Morocco, preventing foreign domination during the early waves of European colonial expansion. Despite pressures from external powers and the changing dynamics of global trade and politics, the Alaouite Dynasty preserved Morocco’s independence and religious integrity, setting the stage for its future role on the world stage.

Morocco was the first nation to officially recognize the United States of America as an independent country. In 1777, during the American Revolutionary War, Sultan Mohammed III of Morocco opened Moroccan ports to American ships and later formalized this recognition through the Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship in 1786. This treaty remains the longest unbroken diplomatic relationship in U.S. history, highlighting the deep historical ties and early international support the young nation received from Morocco.

The legacy of the Alaouite rulers remains a testament to their vision, strength, and determination in unifying Morocco and protecting its rich cultural and religious heritage.

Key monarchs:

Moulay Sharif (1631–1636) – Founder of dynasty in Tafilalt.

Moulay Mohammed I (1636–1664) – Expanded power, fought rivals.

Moulay Rashid (1664–1672) – Unified Morocco.

Moulay Ismail (1672–1727) – Strong central rule, built Meknes.

Moulay Abdallah (intermittent 1729–1757) – Power struggles post-Ismail.

Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah (1757–1790) – Stability, trade, US recognition.

Moulay Yazid (1790–1792) – Short, violent reign.

Moulay Slimane (1792–1822) – Religious reforms, isolationist.

Moulay Abderrahmane (1822–1859) – Modernization, early French conflict.

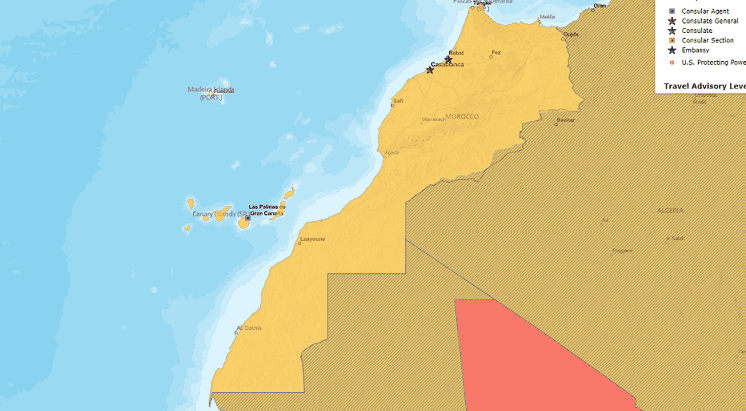

Alaouite Dynasty (1830-Present)

The Alaouite Dynasty (1830–Present) continues to be the ruling family of Morocco, with a remarkable legacy that has shaped the nation's modern history and its position in the world. Since coming to power in the 17th century, the Alaouites have consistently adapted to changing political landscapes, economic challenges, and social transformations, securing their place as Morocco’s longest-reigning dynasty.

During the 19th century, the dynasty faced significant internal and external pressures. While Morocco managed to maintain its sovereignty during much of this period, it began to feel the growing influence of European powers, especially France and Spain, which sought to expand their colonial empires in North Africa. This period saw the Alawite rulers navigating complex international diplomacy, including the signing of treaties that resulted in Morocco becoming a French protectorate in 1912. Despite this external influence, the Alaouite monarchy remained a key symbol of national unity and resilience, particularly through the efforts of Sultan Mohammed V in securing independence in 1956.

Since gaining independence, the Alaouite Dynasty has overseen a series of political, economic, and social reforms. Under the leadership of King Hassan II (1961–1999), Morocco navigated the complexities of the post-colonial era, managing both domestic stability and international relations while addressing issues such as economic modernization, political reform, and territorial disputes. The king's reign marked the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, although real political power remained centralized.

After the death of King Hassan II, his son, King Mohammed VI (2000–Present), ascended to the throne and initiated a wave of reforms aimed at modernizing the country’s political and economic systems. King Mohammed VI has been particularly focused on improving human rights, gender equality, and economic development, while also taking bold steps to revitalize the monarchy's role in governance. His reign has seen major reforms in areas such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, and socioeconomic development, transforming Morocco into a modern and more prosperous nation.

The Alaouite Dynasty’s continued influence in Morocco underscores its ability to adapt to changing times while preserving its deep roots in Moroccan identity, Islam, and the country’s rich cultural heritage. The royal family remains a symbol of unity, continuity, and national pride, with the monarchy playing an essential role in guiding Morocco through the challenges of the 21st century.

Key monarchs:

Sultan Moulay Abd al-Rahman (1822–1859): Defended Morocco from European colonial expansion and modernized its military.

Sultan Moulay Hassan I (1873–1894): Strengthened governance and resisted European influence.

Sultan Mohammed V (1927–1961): Led Morocco to independence from France in 1956.

King Hassan II (1961–1999): Modernized infrastructure, stabilized the country, and reinforced sovereignty.

King Mohammed VI (2000–Present): Focused on economic reforms, human rights, and international relations.

Moroccan Association of Perth

Bridging Morocco and Australia through culture and community.

Newsletter

© 2024 - 2025. All rights reserved.

We acknowledge the Whadjuk Noongar people as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we live and work. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.

Visit our Forest:

Our Stripe Climate Page: